Register Mail Article

By Antwon R. Martin

The Register-Mail

Posted Aug. 3, 2014 @ 6:30 am

GALESBURG — After 55 years, the Galesburg School District is making a gesture toward righting a shameful wrong.

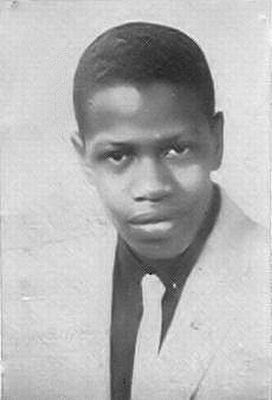

Through the bond of old friends and a night of beer and pizza, come 3 p.m. Friday, Alva Earley will receive the Galesburg High School diploma he was wrongfully denied in 1959.

Owen W. Muelder, director of the Galesburg Colony Underground Railroad Freedom Station at Knox College, leaned back in his chair and looked out the window of his Old Jail office while he conjured memories of the first time he heard Earley’s story.

Muelder and Earley had attended GHS together as well as Knox College for the two years Earley could afford it. The Knox College Class of 1963 was having its 50th reunion during last October’s homecoming and Earley, who now lives as a retired lawyer in La Junta, Colorado, was in attendance along with Muelder and fellow GHS/Knox grad Lowell Peterson.

“As it turns out, a large number of ’63 Knox grads attended either Galesburg High School or Corpus Chirsti High School,” Muelder said. “About a half-dozen of us got together at the Cherry Street Restaurant and Bar.

“As we reminisced that night and recalled the schools we went to in Galesburg and the teams we played on and singing in the choir — all the things you do when you reminisce — Alva Earley, who was with us that night, who is an African-American, told us an astonishing story.”

Even as Muelder recalled his friend’s words 10 months later, his furrowed brow and open mouth illustrated his surprise that night.

“He said, ‘You know, you guys, the night that you marched together at the Galesburg High School Class of ’59 commencement ceremony, I wasn’t allowed to march with you.”

Earley’s story stuck with Peterson so intensely that he asked Earley to write the events in a letter, which was completed and sent out in February.

“Please forgive the form of this letter,” it began, “since my eye surgeries of June, July and November 2013, my near vision is so poor that I can no longer type and know no one who will type a letter for me. Hand writing this letter is both difficult and painful. So, on with it.

“Beginning in 1925 or earlier,” the letter continued, “North Lake Storey Park was off limits to negroes, Hispanics, and Indians. We were given our own park on the south side of Lake Storey,” in what Muelder described as “a little inlet, kind of on the southwestern corner, out of sight from the north beach.”

“Because separate was nowhere near equal,” Earley wrote, “during late April of 1959 a group of black people, myself included, planned to have a picnic luncheon on a Saturday (around May 10th) at a pavilion in North Lake Storey Park. I was to bring a large pan of baked beans.”

It didn’t take long for word to reach the GHS college counselor, however. The counselor approached Earley, a GHS senior at the time, in the high school halls and asked about the planned picnic.

“He then said, “Boy, if you go to the north side of Lake Storey, you will NOT be graduated from GHS and you will NOT go to college,” Earley wrote. The high school senior told the counselor he had already been accepted to both the University of Chicago and Northwestern University.

At the picnic, the group enjoyed an “excellent meal at a pavilion in North Lake Storey Park” despite a crowd of hecklers that had gathered.

The good times didn’t last. In the days following the picnic, Earley received letters from both universities.

“Both letters were short, terse, and quickly to the point,” Earley wrote. “They said something like, ‘It is our regret to inform you that it is NOT our policy to accept a student who is NOT recommended by his high school.’

“I was out! Twelve years of hard work and with one sentence I was out.”

As Earley explained over the phone, growing up with a trying home life and an abusive father pushed him to focus on studies, sports and his after-school job that he worked from 6 to 11 p.m. Monday through Friday and 3 to 11 p.m. Friday and Saturday.

“I was beat regularly after the age of about 4,” Earley said, “and so I told myself I would be as close to perfect as anybody could be.”

During study hall prior to graduation, “the other shoe fell.” All seniors were told to report to the gymnasium to be measured for caps and gowns, but as Earley walked toward the classroom door, his teacher told him to return to his seat and study. She told Earley he would not graduate.

Earley continued school through the last day of classes, though he never received his grades. In June of 1959, Earley stopped by each of his teachers’ homes to ask about his grades. According to the letter, he was given one B, the rest were As.

Without a diploma or transcript, Earley began applying to colleges across the United States. Each school rejected him for reasons such as not being recommended by his high school, not graduating, having a troubled home life, dropping out during Easter break, being a troublemaker and being a convicted felon — the only true statements being the first three.

The last school to reject Earley was Berea College of Agriculture and Industrial Arts in Kentucky. With an SAT score of 490, they had the lowest average out of any school he had applied to. Earley’s was 1,296.

With his direction lost, Earley switched paths and planned to join the Air Force.

During Earley’s last semester at GHS, he had a class with Jim Umbeck, son of Knox College President Sharvey G. Umbeck. Jim knew Earley had been in class every day until the end of the term and was in a position to tell his father something was wrong with Earley’s situation.

Days before Earley’s physical in Peoria, Dr. Umbeck called Earley at home and asked him to re-think entering the Air Force, suggesting instead that he meet with Umbeck and the administration that day.

At their meeting, Earley told them what happened between him and the GHS college counselor, the picnic and the rejection letters. The administrators then invited Earley to become the last member of the Knox College Class of 1963.

“I had a home!” Earley wrote. “A good home!”

Two years later, after his finances dried up and his father forced him to move out, Earley “knocked around the country” for a year or so to earn money. He attended the University of Illinois and graduated with a bachelor of science in the field of physiology before entering law school and receiving a doctor of jurisprudence degree from Chicago Kent Illinois Institute of Technology. In the mid-1980s he would receive a doctor of divinity degree from Northwestern University for his work in service of the elderly in Chicago area.

Even with two doctorates and a career of practicing law, never receiving a high school diploma haunted him.

At one time, Earley aspired to work with the federal government, hoping to eventually become an FBI or Secret Service agent.

“I got shot down so fast,” Earley said. “I didn’t stand a chance and I didn’t understand why.”

When trying to transfer to a federal division while practicing law in the ’80s, Earley was finally told that he would never be able to work for the federal government without a high school diploma.

“I was told, ‘Although your doctorate of jurisprudence proves you have the intellect for a high school diploma, it is our belief that you did something wrong in high school.’?” Earley grumbled as he said the words over the phone.

Though the school district intends to right its wrong in the coming days, it doesn’t change the fact that Earley carried the injustice with him for the better part of a lifetime.

“I will never graduate with my class, wearing my cap and gown, going through the procedure with half the town cheering,” Earley said. “It’s one of the most important things and I missed it and it’s never coming back.”

Looking ahead to Friday, however, he takes some solace in his old school’s gesture.

“This school board is doing the right thing when they don’t have to and I am very grateful for that,” Earley said, adding that the true recipients of his gratitude are Muelder and Petersen for recognizing a miserable situation and making it right.

Having confirmed that Earley passed all the requirements necessary for graduation, District 205 Superintendent Bart Arthur will present Earley with his diploma Friday afternoon as part of the GHS Class of 1959 reunion at the District 205 office building.

“Things have changed,” Arthur said, “and hopefully what we’re doing Aug. 8 shows that things are better now than they were in the ’50s and ’60s.”

As Muelder said, receiving that piece of paper 55 late hardly wipes the slate clean, “but it is, in some small way, an opportunity to — I hope — make Alva Earley feel better.”

Pointing to Galesburg’s founding in the 1830s as a center for antislavery, Muelder described the sad irony of a town transformed into a place where black people were told not to step foot on the white side of a public beach.